In a clip that is quite telling of how far relations between digital-savvy youth and power structures have come; the botched, now incarcerated, heir to Egypt’s throne, Gamal Mubarak, was asked a question on his view regarding the youth of Facebook. The young Mubarak dismissed the question mockingly by asking another reporter to answer it causing the audience to burst out in a fit of laughter. That was prior to the 25 January 2011 Egyptian Revolution. Today, as the leaked photograph of Egypt’s state security (right) illustrates, power structures no longer have as much time to laugh about as they dedicate resources to monitoring the Facebook profiles of young activists and their social media activities.

It was only appropriate that the 13th Mediterranean Meeting in Montecatini, Italy, held on 21-24 March 2012, would have as its first (out of sixteen) workshop devoted to, “Youth and Citizenship in a Digital Age” (directed by Linda Herrera and Peter Mayo). Set at the base of the Tuscan hills, the event brought together seventeen exceptional inter-generational participants ranging from bloggers, researchers, and activists from the fields of politics, arts, and education. They heralded from Egypt, Palestine, Turkey, the United States, and southern Europe.

The stimulating discussions delved into the changing nature of politics and power in the digital era and the rise of new political actors including children. Yet not all the case studies pointed to the politically emancipatory effects of new media: young Egyptians have been employing new platforms and tools to empower themselves for subversive ends whereas youth in Turkey, on the other hand, appeared to be far from utilising this modus operandi. The questions raised by the group revolved around how the young enacted their citizenship in the digital age as a way to both confront power and imagine a different future.

When Youth Defriend the Status Quo

It was at the close of the last century that American education pioneer, Deborah Meier, noted:

There’s a radical--and wonderful–new idea here…that all children could and should be inventors of their own theories, critics of other people’s ideas, analyzers of evidence, and makers of their own personal marks on the world. It’s an idea with revolutionary implications. If we take it seriously.[1]

That was from a 1995 address from Meier on the United States context. Around the same time, across the Atlantic, Arab children were being reared in an era of mounting repressive regimes. Mubarak’s police state in Egypt went into overdrive mode, Tunisia’s Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was “re-elected” with 100 per cent of the vote, and Palestinians were not reaping the supposed benefits of the Oslo peace process and faced a “beautification” of the occupation rather than an end to it. It was business as usual, and the only “makers of their own personal marks on the world” were the Arab dictators. But something happened. Their 33.6k modems started dialing ISPs and soon, youth in Cairo were forming friendships with their counterparts in Alexandria, not to mention wired peers across different continents. Palestinians were discovering new ways to express their cause. While the economic benefits of globalization had bypassed the Middle East’s young generation, the information revolution did not (at least not to the urban centres). The children submerged in the information technology of the 1990s onwards are today’s youth.

The study of youth is an old phenomenon that should be studied in new ways, yet we should also find new ways to understand the old phenomenon. As noted by Linda Herrera, one new way of understanding youth citizenship and media is that media is not passively consumed; instead individuals consumers on platforms that use 2.0 web applications such as Facebook, are also producers of and aggregators of content and part of a new form of public conversation. In other words, they are not the receivers of pre-packaged images and ideologies from state media and schools textbooks, but are the active produces and scrutinizers of content, and this process changes the way they think about and interact with society and the state.

[The wired generation that are defining the concepts of youth

and citizenship Source: Patrick Baz/AFP/Getty Images ]

Demet Luekueslue argued that in Turkey the category of youth emerged as a construct in the nineteenth century as a part of the country’s modernization project led by the founding father of the modern Turkish state, Kamal Ataturk. From this period youth have been defined as a political category charged with fulfilling the modernizing project of the nation. She argues that Turkish youth have not been using new media in the same ways Arabs have, for activities that can be described as politically subversive and oppositional.

Dina El-Sharnouby stood on the other end of the spectrum, noting that while youth were seen as the hope for rebuilding Egypt during the period of President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Pan-Arabism, they have been viewed as a problem since the period of Anwar Sadat’s 1970s Infitah (‘Opening’) policy. El-Sharnouby analysed Egyptian news sources since the turn of twenty-first the century to examine how the government sought to accommodate the "youth bulge." The Mubarak government conceived of youth as prone to laziness and passivity. Moreover, El-Sharnouby highlights that many scholars erroneously thought that disenfranchised youth would turn either to drug abuse or religious extremism. It therefore came as a surprise to them when scores of the “problematic,” “apathetic” and “lazy” youth were the main actors and agents of dissent in the January 25 revolution.

Like the historically-overlooked Children’s Crusade, Chiara Diana injected a fresh perspective into the field by bringing children to the forefront of discussions. In the revolutionary and changeable context of the Arab uprisings, and through social media, Diana made the case that Egyptian children are in the process of developing a deep sense of belonging to their homeland, an acute political consciousness and responsible social and environmental tendencies. All these elements make this generation eager for ways to perform an active and responsible citizenship in post-revolutionary Egypt.

["Armed and dangerous"--Translating the offline world back online on

27 May 2011 in Alexandria. Image: Amro Ali]

In attempting to understand the modest cultural renaissance in the Arab sphere, Catherine Cornet posed the question: “Did this ‘Arab digital revolution’ contribute in creating a cultural revolution within a ‘cyber civil society’ to be extended to society at large? And if it played an active role in the ‘democratization’ of Arab art and culture, how did or could it transform them into major tools of identity change, political awareness, and/or economic well-being?” Cornet argues that the real revolution occurred with the merger between new media in the Middle East and the spectacular development of youth culture after 2001 on the one hand, and the natural individualistic orientation of new media that, from the beginning, espoused artistic exploitation of the self. The result has been a new generation of Arab artists who monetize their work directly online, not mediated through galleries or other parts of the artistic establishment.

A Question of Citizenship

Among the core questions addressed in the workshop was if the nature and attributes of citizenship have changed in the digital era. Rehab Sakr noted that there are four elements of citizenship: membership, duties, rights, and participation. Additionally, she highlighted that digital citizenship is merely an extension of the concept to a new era, with the new dimensions being that it refers to a deterritorialized space. Miranda Christou and Elena Ioannidou provided an anti-citizen case by looking at how groups that reject the nation construct, ideological spaces, and transnational networks. They examined what they called the darker side of digital politics and citizenship through a case study of the right-wing movement in Cyprus (ELAM). They traced how the movement uses the internet to network with similar organizations to promote racist and far-right ideological convictions.

Citizenship in the context of a nation state versus virtual citizenship was a matter discussed at length. Palestinians, in the absence of a homeland with full autonomy and rights, have no choice but to build an online community.

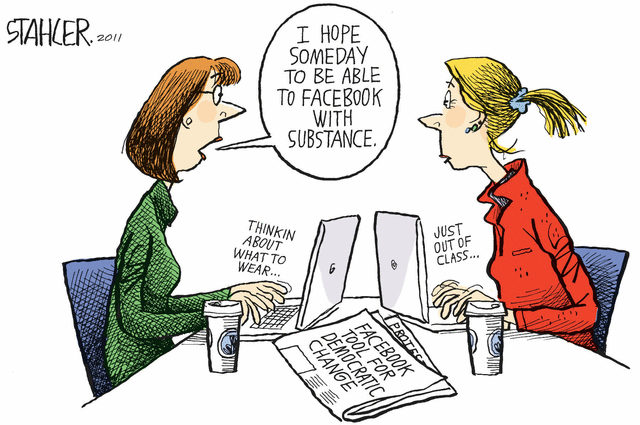

[Arab youth are ahead of the world in their cutting-edge

use of social media. Cartoon by Jeff Stahler/Cagle Post]

Mira Nabulsi expanded on the unique case of the Palestinians. She noted that in 2009, Gaza ranked third on Twitter’s top of “News Events” tweet trends. Like other social and political movements around the world, Palestinians and pro-Palestine groups have been actively using the Internet to spread the word on the political and humanitarian situation in Palestine and the Palestinian people. Those who blog, tweet, or share content related to Palestine on the web are not only Palestinians or Arabs, but a diverse group of international human rights advocates, anti-war activists and the supporters of Palestinian rights. Whereas manifestations of digital activism or electronic resistance may take multiple forms and use different platforms, social media are increasingly becoming the space for transnational and global activism for Palestine. Through social media, Palestinian youth are exerting and waging their struggle to claim their movement, identities, and rights.

["Rebels in Arms"--Social media tools have become the Kalashnikovs

of the 20th Century. Cartoon by: Emad Hajjaj/Cagle Post]

Reinforcing El-Sharnouby’s argument regarding the marginalization of youth, Hisham Soliman spoke of a pre-revolution identity crisis that permeated Egypt’s young population and made citizenship and national feeling count for very little. Scores of youth, especially young men, considered emigration as one of the only solutions. But the new media allowed them access to new spaces and empowered them with new techniques to redefine their senses of identity and belonging. Instead of keeping them in their private spaces, it allowed them virtual alternative spaces that compensated for the absence of an actual public space. It even provided them with the means to aggregate and to later claim back the actual public sphere. Soliman is working on a typology to explain new forms and categories of citizenship in the digital age.

Who’s got the Power?

“Is the nature of power changing in the digital era?”

Such was a question posed by Herrera. She probed whether power structures and ways of exercising citizenship in the digital era are really new, or do we just believe them to be so? Are young, tech-savvy political actors acting as countervailing forces to elite economic and political power? As Herrera highlighted, if Egypt’s youth pose a challenge to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), they also pose a challenge to the United States. Therefore in understanding internet usage, it is important to put the individual within a context of global forces. Within this context, questions of political change become important. When and how can individuals and groups penetrate structures of power? In what ways can sitting in a coffee shop and tweeting be considered “doing activism?” As Sakr noted, “Online movements depends on offline actions.” These questions led to wider discussions in the group about how people occupying virtual and physical public spaces—whether Facebook or Tahrir Square—can not only challenge power, but arrive at alternative social and political economic arrangements. Shimaa El-Sayed Hatab further addressed these questions as she sought to “uncover cycles and processes by which forms of contentious politics generate legacies and contentious trajectories, as well as the interplay between state’s structure and social energies.”

Decentralization emerged as a key topic. Amro Ali brought up a different form of decentralization using Egypt’s second largest city, Alexandria, as a case study. The notion that geography and placement of venue-driven agents of socialization (as in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina) should always be added to the equation of how the informal public translates the “ecosystem” developed in social media onto the street level. Moreover, Ali shows with maps of the city how the coastal city’s protest styles have been forced to accommodate to the linear grid landscape that has not been as mass-friendly as Cairo’s Tahrir Square.

Another dimension was added to the offline-online correlation; Sonali Pahwa gave intimate accounts of two young girls, Eman and Fatma, by transposing the model of the salon to blogs on the Egyptian Internet. Pahwa emphasised that this salon is just as productive space of public discourse as media typically associated with the public sphere. Both Eman and Fatma used their personal voices to convey intimate knowledge of national and gender politics. Once inside, the reader could experience the conflicts that the blogger faced in translating feelings into opinions, and personal experience into a public stance. As the bloggers took on the role of authoritative commentators, the reader could see how the roles of private citizen and public figure were overlapping in contemporary Egypt.

A limitation of virtual media is its inability to give rise to a coherent discourse and set of ideas. Online activism might even be inhibiting deeper thinking and analysis of complicated political and economic problems. Alession Surian discussed this matter at length in his presentation: “Youth 2.0: beyond the Faustian Bargain.” Surian took a much more critical approach in questioning whether social media is making us feel good without a level of involvement in light of, for example, click activism petitions? Surian, drawing on arguments made with regard to “filter bubbles” argued that the individuals, through Google searches and Facebook filters, are being locked into patterns. Facebook and Google become familiar backyards, leading to reduced thinking and a closing rather than opening of ideas and social spaces.

The Way Forward

The workshop was, in the participants’ view, a tremendous success. The cross-exchange of ideas, practices, and case studies were fruitful to the extent that the workshop members agreed to contribute their papers towards an edited book.

Peter Mayo poignantly brought the perspective of Antonio Gramsci into the discussion. Gramsci states in his Prison Notebooks:

If the ruling class has lost its consensus, i.e. is no longer leading but only “dominant,” exercising coercive force alone, this means precisely that the great masses have become detached from their traditional ideologies, and no longer believe what they used to believe previously, etc. The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.

Some eighty years later, the morbid symptoms in the hegemonic structures are forcing up the emergence of new actors who are employing new technologies, reappraising citizenship, and acquiring fluctuating forms of power. It is this generation that will be the pioneers of nurturing an enabling and disabling environment for policymakers and elites at home and abroad.

[“The Past Meets the Future”--David Horsey`s cartoon/Hearst Newspapers]

_________________________

Notes

[1] Deborah Meier, The Power of Their Ideas: Lessons for America from a Small School in Harlem (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995) 4.

13th Mediterranean Research Meeting

Youth and Citizenship in the Digital Era

Firenze, Italy, 21-24 March 2012

WORKSHOP #1 SCHEDULE

INTRODUCTION

Linda Herrera

Perils & Promise of Information Age

Rehab Sakr

Citizenship in the Digital Age

Peter Mayo

Critical Pedagogy in the Digital Era

COMMUNICATIONS & POLITICS OF CULTURE

Catherine Cornet

The Digitally-Mediated Democratization of Arab Youth Culture Trough The Social Networks And New Media After 9/11: Pre-Announcing revolutions Singing, Painting, Filming And Posting It All

Sonali Pahwa

A Blog of Ones Own: Women’s Homes on the Egyptian Internet

Charis Boutieri

Virtual Learning and Virtual Intimacy: Emerging Youth Socialit(ies) in Morocco.

Dina El- Sharnouby

Youth: Problem or Solution? Egyptian Youth’s Conceptualization Before the Revolution

INTERNET, IDENTITY & RESISTANCE

Demet Lüküslü

Internet as a rich source for understanding political attitudes of contemporary young generation in Turkey

Miranda Christou & Elena Ioannidou

Constructing Ideological Spaces & Transnational Networks through the Internet

Mira Nabulsi

Palestine Online Activism: Negotiating Identities, Reclaiming Rights, Catalyst of a Youth Movement?

Chiara Diana

Building a Political World of Egyptian Children and Young Generations in a Digital Era

SOCIAL MEDIA & REVOLUTION

Rehab Sakr

Between Virtual Citizenship and Digital Citizenship: an Experience from the Egyptian Revolution, Case Study of R.N.N. Rassd ‘monitorint’ Youth News Network on Facebook

Amro Ali

Revolution Upgrade: the Case of Alexandria’s Digital Youth

Shimaa El-Sayed Hatab

Egypt’s Revolution: From “Technological” Revolution Towards More Comprehensive Understanding

Hisham Soliman

Youth and Citizenship in a Digital Era

YOUTH 2.0, EDUCATION & WORK

Linda Herrera and Peter Mayo

The Arab Groundswell, Digital Youth, & The Crisis of Education & Work

Hasan Hüseyin Aksoy

Technology Competency For What: Experiences Of University Youth Using Virtual Space For Struggle Against To Oppression*

Alessio Surian

Youth 2.0: Beyond the Faustian Bargain